Family Day Workshop Preview: Jennifer Moon

With just over a week until this year’s annual Family Day on August 19, we are crossing our t’s and dotting our i’s finalizing all the details of the big day. I met up with another one of this year's participating artists, Jennifer Moon, for an interview and demonstration of her Family Day workshop. You may remember Jennifer and her work from 2014, when she was included in Made in L.A. and led a workshop during Family Day. This year’s theme "Art for Good" directly relates to her overarching mission as an artist—to utilize the potential that art has for transformation and revolution. In this workshop, participants will be invited to transform into an empathy superhero by making a costume with Jennifer Moon.

Isoke Cullins: Could you tell us about yourself and your artistic practice?

Jennifer Moon: The tagline on my website says "artist, adventurer, and revolutionary." I also do a lot of writing. My work involves looking into how experiences and certain beliefs affect the way I perceive myself and others. And trying to work through that as a way to clear these belief entities that are often created through oppressive structures, so that I can then see myself in a loving way and see others in a loving way.

IC: Where did you grow up? Where are you currently based? And how have these places influenced the art that you make and inform the way you approach your work?

JM: I grew up mostly in Orange County. I’m currently based in Culver City, not that far from the Hammer. I was born in Indiana, and my parents and I moved to California before I turned one, so I grew up in California most of my life. I came to Los Angeles to go to school at UCLA and then to ArtCenter, and I’ve stayed in L.A. since. There’s a certain openness that I feel here in the city and in the way it’s laid out—the varying environments, from the beach to the desert to the mountains. I was also very influenced by the schools that I went to. When I went to UCLA, my program had somewhat of a loose structure. It was more practice-based than theory-based—about making stuff and pulling inspiration from whatever. I think that helped me to be able to pull from popular culture, science, self-help, and political theory like I do now. That sort of openness to explore is something that was really influential to me.

IC: How did you come into your artistic practice? Did you study it formally or were you exposed to it a lot as a child? What moment did you decide that you wanted to be an artist?

JM: I went to a high school in Orange County that was temporarily the Orange County High School of the Arts. I always really admired the artists, but I didn’t think I was good enough to be an artist because I couldn’t draw technically well. And my idea of art in high school was very technical—drawing well, painting well, and making objects that look realistic. I always aspired to be an artist, but also felt less than and like a poser.

I think getting into UCLA was one of the luckiest things that ever happened to me. I wrote an essay on a Van Gogh painting and talked about the feelings that it evoked in me after seeing the painting in person. It was a formal essay, in that it talked about texture, composition, and color. I got in, and once I was at UCLA my whole perspective shifted. I went to the Helter Skelter show in 1992 at the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, and it destroyed my previous notions of art. In that show there were all these installations and works that were not what I considered art. So it made me think: this is art? It was then that I was able to realize that I can be an artist, too.

IC: What themes does your work address?

JM: A lot about love, in all its many formations. I tend to bring in my personal experiences and make work about it in a way that’s accessible—for example, how is love performed and enacted in various relationships and settings, like the love between within like a family versus love for humanity? How are those things different? And why are they different? How I love humanity or service to humanity sometimes doesn’t translate to the love I have for something personal, because sometimes the personal love is riddled with control, jealousy, or possessiveness. That’s curious to me. What are the factors involved that make it happen that way? And why? How do I participate in that? What can I do to shift that and maybe make those various forms of love more aligned in a healthy way?

IC: What does revolution mean to you?

JM: Revolution is a complicated term because it means different things in different cultures and in different histories. The way that I use it relates back to science. I call the matrix that we live in "the 5% universe," and the idea comes from the notion of "dark matter" and "dark energy." In cosmology, dark matter and dark energy are unknown substances and energy forces that we can’t observe, but we know they exist because of their effects on celestial bodies that we can observe. It’s interesting because this unknown substance and energy force make up 95% of the universe. So we exist in this 5% universe with a very limited perception. When I think about revolution, I’m thinking about how we can expand beyond the 5%. By asking this question, first I have to identify the systems that keep us bound to the 5%. I often talk about it in terms of systems that are rooted in binaries, hierarchies, and capital. Any kind of interaction that perpetuates or creates new binaries, hierarchies, and capital keeps us locked in this space. It’s difficult because our most fundamental tool—language—is grounded in binaries, hierarchies, and capital. So to me that’s the ultimate revolution—to be able to discover ways to exist outside of these systems and ultimately the 5% universe.

IC: What made you interested in participating in Family Day, and how do you relate to this year’s theme?

JM: I love kids. I used to work at a preschool, and I believe—like Whitney Houston says—the children are our future. Within my overarching project of "the revolution," there are different factions. One of the factions is creating an alternative education system. I’ve always imagined a league of child geniuses—kind of like a superhero league of children. It’s fun to imagine children having discussions about how to save the world as revolutionaries, because children are amazing. The focus for this year is "Art for Good," and I do really believe that art has the potential for transformation that is not available or accessible in other disciplines. I also participated in Family Day in 2014, and it was really fun.

IC: Can you explain how your workshop will help participants to become "Empathy Superheroes"?

JM: The idea for the Empathy Superheroes workshop originated from something my friend Michael Blomsterberg once said, combined with what I’ve read about the "Second Brian" in our guts. He said that most people aren’t having relationships with each other, but rather our beliefs are having relationships with one another. When we look at violent conflict, it is generally a conflict of beliefs.

Then I learned about the Second Brain in our enteric nervous system, which is an extensive and plentiful network of neurons lining our guts that some scientists believe exists to listen in on the 100 trillion microbes (gut fairies) that reside there. There is also research linking emotions to our Second Brain. The idea is that empathy occurs when we can begin to see each other beyond our beliefs, which means feeling each other via our Second Brains.

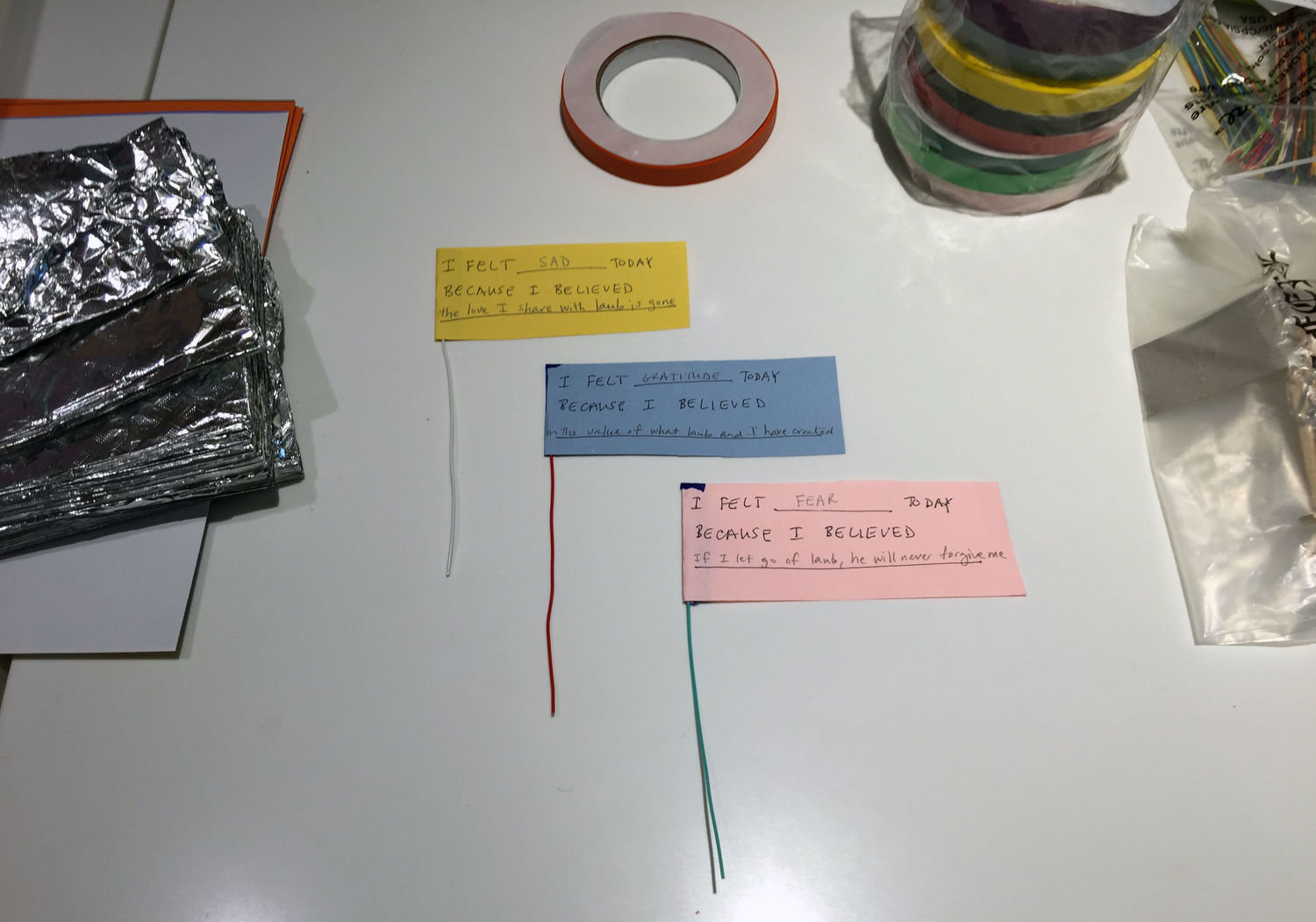

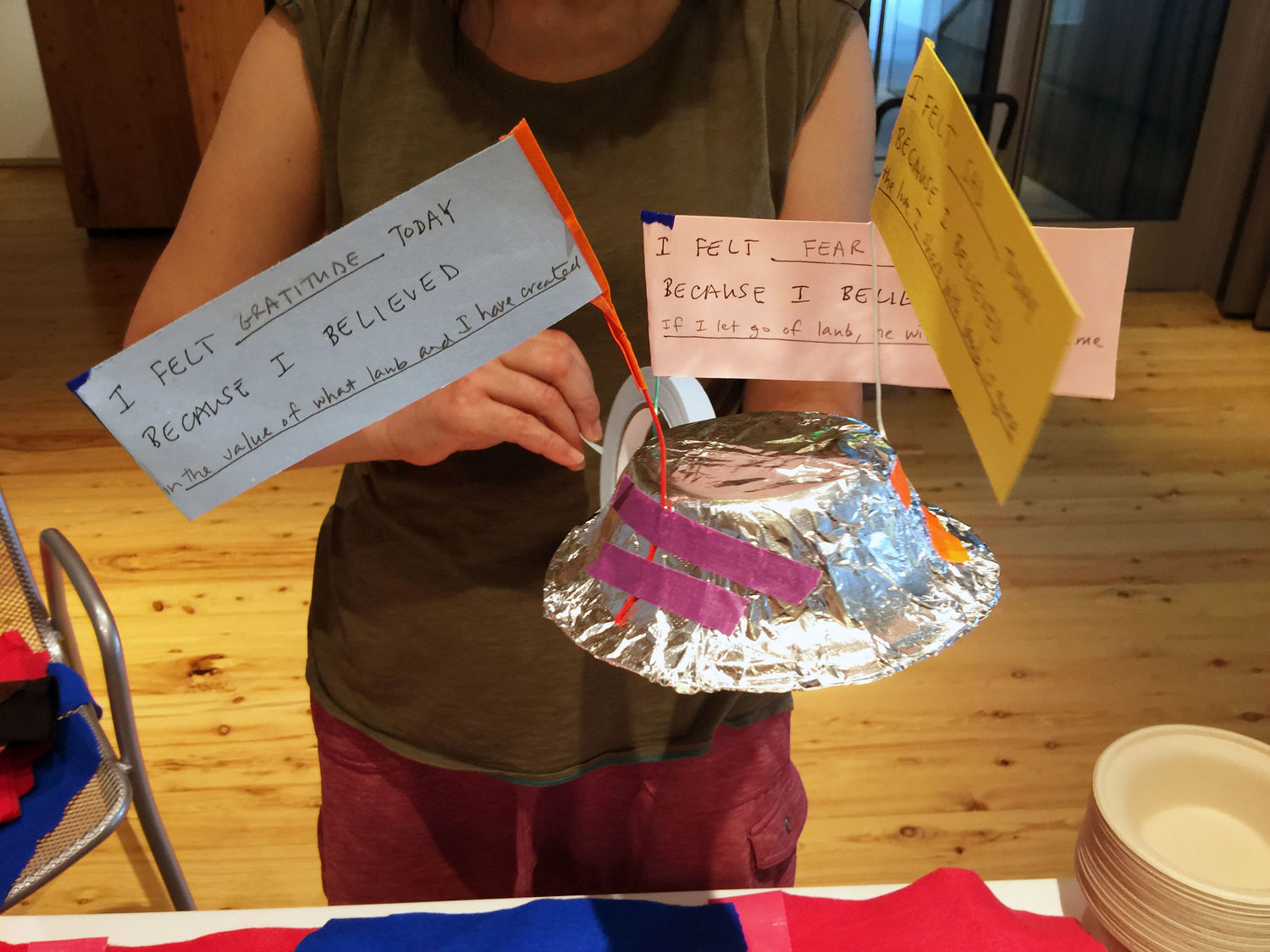

This workshop is designed to focus on one’s emotions or the emotions of others. Oftentimes we experience our emotions without an understanding of where they are coming from, and so we are left to create our own narratives. This workshop will hopefully facilitate sharing the beliefs behind our emotions so that we can avoid compounding belief upon belief. This is the helmet component of the workshop.

For the second component, the participants will be invited to create a belt made of a tactile or visual representation of another person’s emotions (once the belief behind the emotion has been extracted, so to speak). Empathy, as I’m describing it, is essentially feeling and intra-acting beyond beliefs, which is super challenging and perhaps nearly impossible (though I advocate to exist in the impossible)—which is why empathy is a superpower!

Family Day: Art for Good is on Saturday, August 19 from 11 a.m.–3 p.m. The event is free and open to the public.